Bankers: What is Your “Well-Capitalized?”

TKG has had the distinct impression that the bank regulatory community is not pleased with certain limitations and exemptions from Section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act, the section that covers leverage and risk-based capital requirements.

Why do we think this? In a Consent Order dated August 20, 2014, issued by the FDIC and the Alabama State Banking Department against Alamerica Bank of Birmingham, Alabama, the Order sets a leverage ratio of at least 9% and a total risk-based capital ratio of at least 12%. These “at least” levels are commonly referred to as Individual Minimum Capital Ratio Requirements, or IMCRs.

But the Strategic Planning article within the Alamerica Consent Order also states (TKG emphasis added in italics): “At a minimum, the plan shall establish objectives for the Bank’s earnings performance, growth, balance sheet mix, liability structure, capital adequacy, and reduction of nonperforming and underperforming assets, together with strategies for achieving those objectives. The plan shall also identify capital, funding, managerial, and other resources needed to accomplish its objectives.”

In other words, Alamerica’s Strategic Plan shall identify the capital needed to execute its Plan while considering the IMCR mandated by the Consent Order. While we question the “I” in the “IMCR” acronym because we see the 9% and 12% levels pop-up in a high percentage of regulatory orders, the regulators have stated what they believe the capital needs are in addition to asking “what is your ‘well–capitalized’?”

This begs the question of how much capital do you need to execute your strategy? The answer depends a lot upon who you ask. If you ask TKG, the level of capital needed by a depository institution cannot be simply mandated by a regulatory order or directive independent of strategy. It depends on the risk of the assets and liabilities you have or will have on your balance sheet, as well as the off-balance sheet items during your strategic planning horizon.

In our past writings, speeches, and meetings with clients, TKG has written and spoken often about an allocation of capital to balance sheet, and off-balance sheet items, based upon the conceptual framework outlined in Risk Adjusted Return on Capital, or RAROC.

We understand and believe in the need for capital adequacy to be measured in a consistent and reliable manner. But our thinking on capital planning has evolved as we speak to bankers about their perception on risk inherent in their balance sheet now and into the future as part of our capital planning services. We continue to refine how capital is measured and allocated to meet regulatory minimums and absorb potential future losses without falling below regulatory guidelines.

Traditional stress testing methodologies used by Advanced Approaches Organizations (“AAO”) (such as J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., Inc.), in response to CCAR and DFAST requirements to measure capital and risk, are too cumbersome for community banking organizations. Such methodologies evaluate multiple stress test scenarios, fundamentally focusing on how these assumptions result in changes in capital levels relative to some “base case.”

For smaller banking organizations (from $100 million to $10 billion in assets), there are numerous stress testing approaches to consider that are the foundation of capital planning and capital allocation processes. There are many third-party firms that provide credit stress testing, interest rate risk stress testing, or liquidity stress testing for banking organizations. Frequently though, a smaller bank does not “unite” these results into a cohesive capital allocation process or capital plan, and capital adequacy (or lack thereof) is a function of loss, which is potentially not the same as risk.

We suggest a different yet complementary approach to determining your capital level needs based upon your institution’s unique circumstances and strategic direction.

Let’s revisit RAROC. Originally developed by Bankers Trust in the 1970’s as a means to allocate capital on a risk-adjusted basis, RAROC has received occasional commentary from regulators. The FDIC in a winter 2004 Supervisory Insights article titled “Economic Capital and the Assessment of Capital Adequacy” noted “economic capital is a measure of risk”, further stating “model results are expressed as a dollar level of capital necessary to adequately support risks assumed.”

RAROC, mostly used at a point-in-time to evaluate customer, product or division risk-adjusted performance, can be modified so that the focus shifts to economic capital and not on expected returns on capital. Using an economic capital approach, capital assignment percentages are based on a wide range of outcomes. Capital assignment to a particular balance sheet item is driven by management’s assessment of the risk inherent in balance sheet and off-balance sheet items.

TKG’s economic capital approach is also dynamic in that capital assignment, risk weightings and risk levels can change as management’s expectation of risk changes. The assumptions can then be applied to a projected balance sheet to evaluate economic capital based over a number of future periods, not just a point in time. Importantly, the assumptions result in economic capital estimates that are driven by business strategy and risk appetite and not solely on past activities and the specter of stress. In many respects, economic capital is aligned with fair value concepts and the risk buffers that are becoming reality under Basel III.

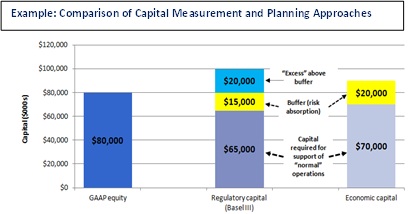

The example below is an extremely simplified look at a hypothetical $1 billion asset institution that has $80 million in GAAP common equity and has $100 million in total risk-based capital as measured under Basel III. Traditional capital allocation planning would then apply losses against the GAAP equity, and other stresses against the regulatory capital measures. The result is that GAAP equity and Basel III measures will decrease and asks “what do we have to do to plug the hole?”

However, the use of economic capital indicates that this institution needs $70 million in capital under normal operating conditions and would need an additional $20 million under stress events. Relative to GAAP equity, and assuming no change in the business strategy or balance sheet composition of the institution, $10 million in incremental capital would be needed to absorb the risk inherent in the strategy. Conversely, such an analysis could identify excess capital in your organization, which would merit serious consideration of an increased dividend or a share buyback program over the strategic planning horizon. In the simplest of terms, economic capital is forward looking to show what capital levels are needed to support strategy, not plug holes.

The addition of economic capital as a measurement tool provides yet another viewpoint on capital management in relation to both GAAP and regulatory approaches. While Basel III has been live for AAO since the first quarter of 2014, it becomes a reality in the first quarter 2015 for practically all other depository institutions.

For capital measurement and planning purposes under Basel III, credit loss and interest rate risk modeling will continue to be used. But simpler concepts based on your strategy, such as that of economic capital, can help your institution to be prepared to answer the question “What is your ‘well-capitalized’?”

Click here to view full TKG Newsletter