Failure is OK

On Friday, April 26, 2024, the Pennsylvania Department of Banking and Securities (the “PA Department”) took possession of Republic First Bancorp, Inc. unit Republic First Bank (“Republic”) due to Republic’s “unsafe and unsound condition.” The PA Department appointed the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (“FDIC”) as receiver, who then struck an agreement with Fulton Financial Corp. subsidiary Fulton Bank to acquire substantially all of the deposits and assets of Republic First Bank.

Republic is the only bank failure so far in 2024. Depositors will have unfettered access to their accounts at Fulton Bank. They were not harmed. This has largely been the case in bank failures since the existence of the FDIC dating back to 1934.

In the recent past, Republic had been embroiled in a boardroom brawl over strategy leading to the departure of Vernon Hill (formerly of Commerce Bank of Cherry Hill, New Jersey fame). In executing a classic Vernon Hill retail bank strategy, Republic’s deposits soared from $3 billion in 2019 to $5.2 billion in 2021. Republic’s loans did not keep pace and the loan to deposit ratio fell below 50%, leading to the purchase of investment securities, which did not age well during the Fed tightening in 2022 and 2023. At December 31, 2023, the Bank’s accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI) was a negative $187 million. Note that the management team at the time of Republic’s demise was not the same team that orchestrated the strategy leading to the demise.

Over the past year and after Vernon Hill’s departure and other Board and management changes, Republic had been trying to raise capital (albeit far less than needed to save Republic) amidst its declining fortunes and mounting losses. When it failed to close a small financing deal in February 2024, regulators had seen enough. Should we be worried?

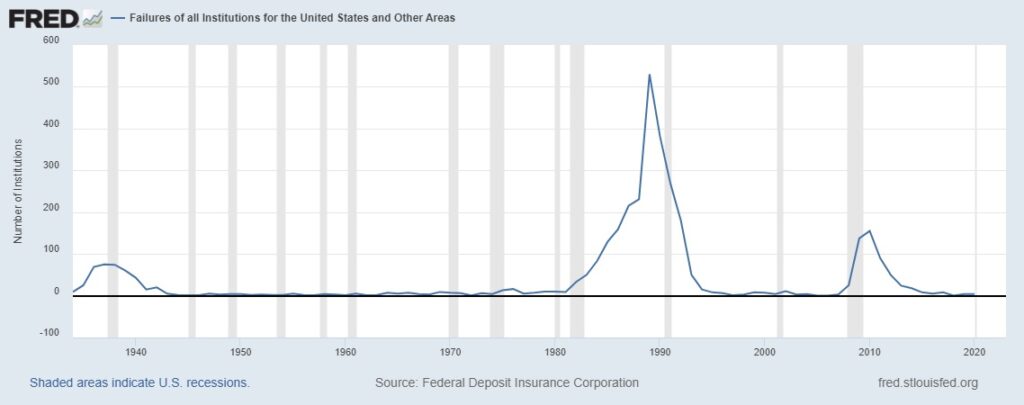

Bank failures are at historically low numbers. In 2023 there were five, three of which were high profile and significant in size. Regulators, bankers, and industry advisors were fearful of contagion due to the rapid runs on Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank (an unfortunately similar name to the Philadelphia bank). The contagion never fully materialized as the U.S. Treasury provided liquidity and more importantly, bankers worked tirelessly to reassure depositors that their deposits were safe. The concern, however, was palpable.

Prior to 2023, it had been over two years since a bank failed. Remember Almena State Bank, First City Bank of Florida, The First State Bank (West Virginia) or Ericson State Bank? Probably not. They were the failure class of 2020. Bank failures did not excite us then. Why should they now?

In retrospect, the rapid run on deposits and the manner in which the run occurred had us questioning if this could happen to other banks. You would have been hard-pressed to find depositor lines wrapping around a block at an SVB or Signature branch because the lines happened virtually. There was no George Bailey behind the teller line trying to calm depositors. But with all of the hype around those virtual runs, and the astronomical levels of uninsured deposits at those failed institutions, depositors were still made whole.

In some respect, we have been a victim of our own success running profitable banks leading to a healthy banking system that incurs historically low failure rates. Because a bank failure now seems like a special event that requires headlines, discussion, and hand wringing as to what went wrong.

In the United States, there are approximately 595,000 business failures per year. Eighteen percent of businesses fail in their first year, and 50% fail within five years. Approximately one tenth of one percent of FDIC-insured banks failed in 2023.

Being the contrarian that I sometimes am, I find this number to be too low. Because innovation requires business models that may be unique. Unique and untested business models could result in calamity. So long as the equity holders end up holding the bag, let calamity come. Evolution requires us to try, fail, and try again.

Regulators, of course, are in the business of limiting failures to protect the deposit insurance fund. So trying unproven business models receives enhanced scrutiny (like banking as a service models are finding out). Especially if the business model exposes the entire bank, rather than an innovative product or line of business that might occupy, say, ten percent of the balance sheet. Having a diverse and somewhat liquid balance sheet, however, did not help Republic.

The challenge with the try, fail, and try again method in banking is that we are not chartering very many new banks as the cost to entry has risen to $40 million or more to start one. So there is very little “try again.” Capital requirements for startup banks can be onerous, and not attractive to investors that can more easily achieve a greater return on their investment by turning to an index fund. They would enjoy greater liquidity too. The level of capital required surged after the financial crisis of 2008-09. Many of the bank failures during that period were relatively new banks operating in hot real estate markets.

In their zeal to limit bank failures, regulators want more capital in de novos. Only four banks were started in 2023. Four. In spite of the low number of startups, we are seeing some uniqueness in business models. Bank of Bird-in-Hand in Pennsylvania started in 2013 focusing on the Amish community. It is now $1.3 billion in total assets.

Innovation is also happening with existing bank charters. Aaron Graft assembled an investor group that recapitalized Equity Bank in Dallas in 2010, ultimately renaming it TBK Bank. TBK focuses on the payments challenges in the independent trucker industry. A very specific niche. In 2010 the bank had $250 million in total assets and $37.5 million in total equity. Today it has $5.6 billion in assets and $980 million in total equity.

What we don’t want to do is inhibit the type of innovation that is happening at new banks, like Bank of Bird-in-Hand, and existing banks, like TBK. Both are healthy and profitable. Bowing to plain vanilla business models encourages consolidation because scale will be the only thing left to distinguish one financial institution from another. And those unique banking needs of Amish or truckers will be left to large banks making decisions about how best to serve them from Charlotte or New York City.

We should not fear bank failures nor overreact in the increasingly rare cases when they happen. We should cheer innovation in banking, and our uniquely American banking system.

Click here to view printer-friendly version.

This TKG Perspective relates to our Strategic Management service, click here for more information.

To receive our TKG Perspective and other TKG content, subscribe at the bottom of this page.